Dennis Eckersley, Doug Harvey, and Game 1 of the 1988 World Series

- Updated: February 20, 2015

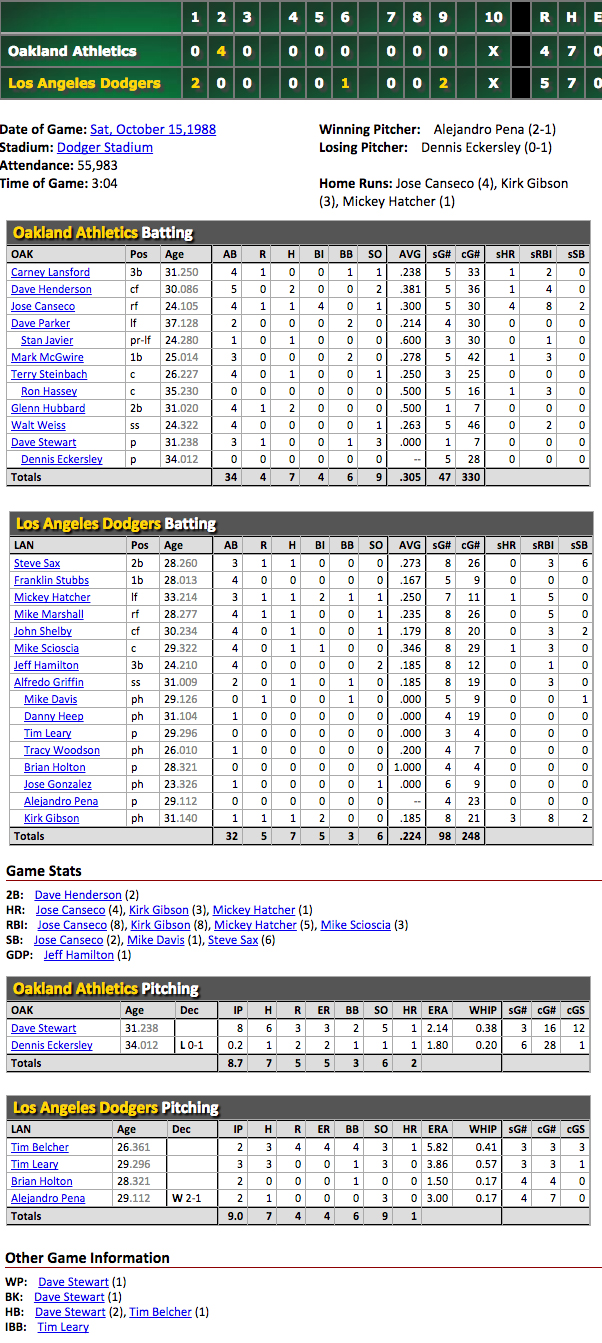

Earlier this week, I wrote about Vin Scully returning to the Dodgers in 2015. During research, I re-watched Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, which, of course, is a classic. Kirk Gibson. Dennis Eckersley. Mike Davis. Tommy Lasorda. Vin Scully. Doug Harvey.

Doug Harvey?

Doug Harvey.

Harvey was the home plate umpire when Gibson launched the now-ubiquitous bomb. While much has been made of Gibson (bad knees, weak swings, and that fist pump around second base), and Scully’s famous call, Harvey factors in to the game much more than I realized. So let’s re-visit October 15, 1988:

00:12 – Vin Scully has the call with Joe Garagiola. Scully had already worked for the Dodgers for 38 years by 1988, and he’ll work at least 27 more. Garagiola, a former big league catcher, left NBC after 1988 and never called another World Series. He broadcast for the Arizona Diamondbacks until his retirement in 2013.

00:22 – The A’s have two new players on the field for the 9th inning: catcher Ron Hassey, and pitcher Dennis Eckersley. More on Eckersley in a minute. Hassey, who would later coach in the Rockies, Cardinals, Mariners, and Marlins organizations, won a World Series in 1989 when the A’s defeated the Giants. After losing the 1990 World Series to Cincinnati, Hassey retired with the Montreal Expos in 1991. Interestingly, he’s the only catcher in Major League history to catch two perfect games – Len Barker in 1981, and Dennis Martinez in 1991.

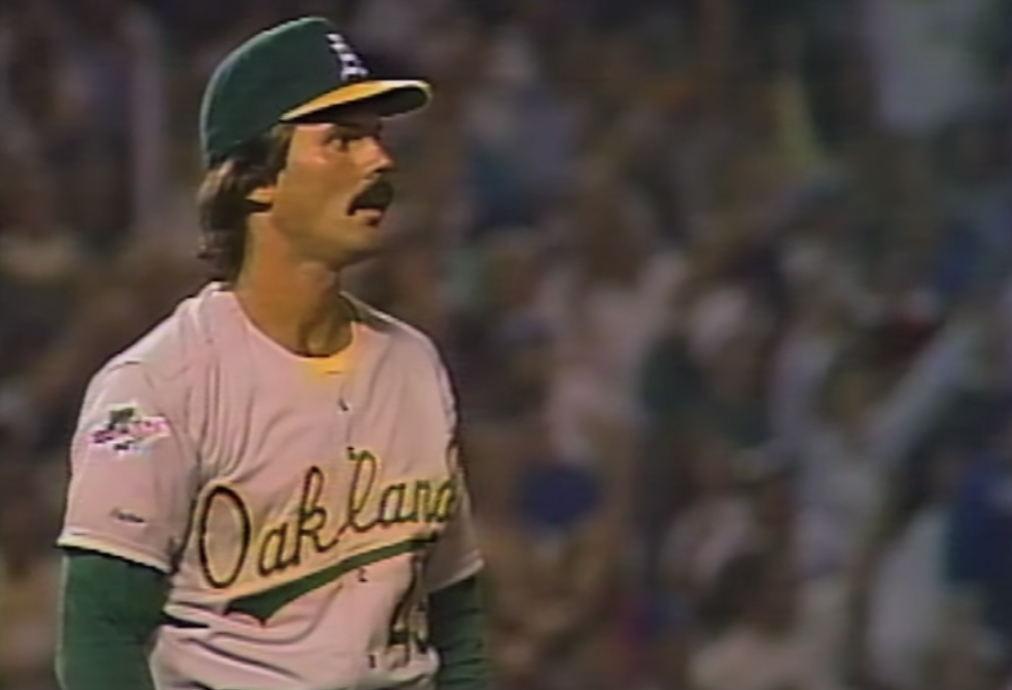

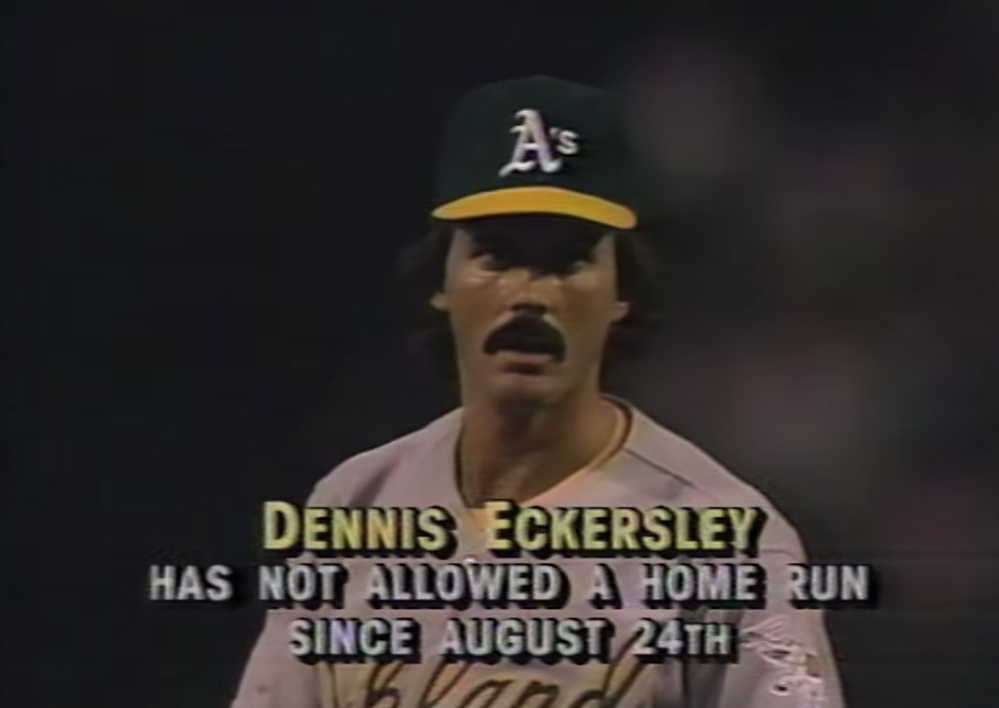

00:29 – Eckersley. Scully and Garagiola focus on Eckersley’s gaudy save total, making light of how he never throws more than two innings per appearance, and rarely throws more than one. Nowadays, one-inning closers are the norm, but in the 1980s, many closers were still throwing two and three innings per outing.

00:45 – Mike Scioscia leads off and watches ball one. Scioscia, of course, now manages the Anaheim Angels. Hired November 18, 1999, he is the longest tenured manager in the big leagues (more than seven years longer than the next closest pair, Giants’ skipper Bruce Bochy and Padres’ leader Bud Black).

01:00 – Scioscia pops up on a 1-0 count. Walt Weiss catches it at shortstop. Speaking of managers, Weiss is a manager himself, running the Rockies for the last two seasons.

01:09 – Scully and Garagiola are still lamenting Eckersley’s one-inning saves. So I looked it up. On the ’88 Dodgers, three guys earned the bulk of saves. Jesse Orosco had nine saves across 55 games and 53 innings. Jay Howell had 21 saves across 50 games and 65 innings. Alejandro Pena had 12 saves across 60 games and 94.1 innings. Eckersley, for the A’s, threw 72.2 innings across 60 games and picked up 45 saves.

Pena was clearly extended a bit (he averaged nearly 1.2 innings per appearance), but Howell (1.1 innings per appearance) and lefty-specialist Orosco (under an inning per appearance) are right in line with Eckersley (just under 1.1 innings per appearance). Not sure why Scully is stuck on this one, but in this case, the numbers don’t quite legitimize his incredulity.

01:30 – With one down, Jeff Hamilton comes to the plate. Hamilton slashed .236/.268/.353 in 1988, numbers which are remarkably close to his career averages across six seasons, all with the Dodgers. He’s in for a tough at-bat tonight, but at least he was a warrior on the mound once in Houston.

02:30 – Good afternoon, good evening, and good night, Jeff.

02:48 – Mike Davis pinch hits. By this point, Eckersley has gotten two outs on five pitches and he’s ready to cruise through Davis to a game 1 victory for the A’s.

03:07 – Davis had an awful year in 1988, slashing .196/.260/.270 in 310 plate appearances. He was even worse as a pinch hitter, going 5-for-30 (.167), and he hadn’t had a hit in a postseason game since 1981. All Eckersley had to do was pitch to him.

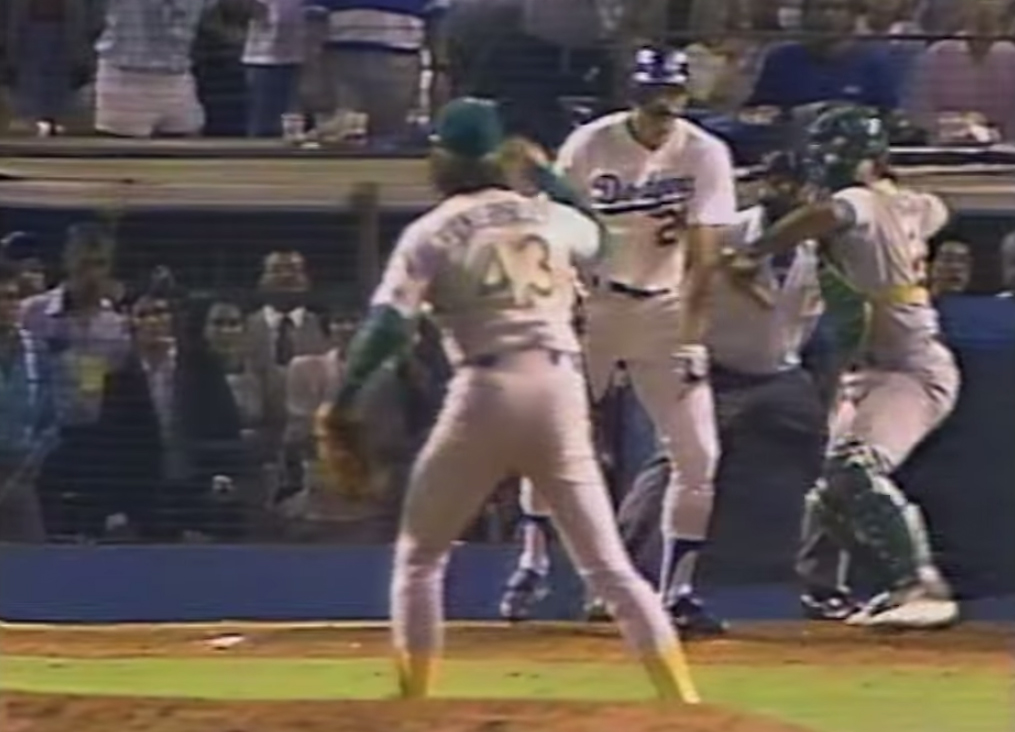

03:15 – The key sequence of events begins here. Davis takes cuts outside the box while Eckersley waits. Eckersley worked quickly his entire career, and was working very quickly on this night. Davis takes his time, no doubt trying to collect himself (at this point, he’s the Dodgers’ last chance). He finally he steps in with both Eckersley and Hassey waiting.

03:26 – Eckersley gets going. Davis isn’t ready and calls time. As late as the request came, umpire Doug Harvey granted it, even though Davis didn’t ask until Eckersley was already nearly to his balance position! The time request is so late that Eckersley doesn’t see it, can’t stop his motion, and throws the pitch anyways. It doesn’t count. It would’ve been strike one. Harvey points to Davis and nods to Eckersley, as if to say, “he called it and I granted it.”

03:44 – Davis fouls off a fastball for actual strike one.

03:48 – Harvey throws Eckersley a new ball, and things get really interesting. Eckersley immediately rejects the ball, throwing it back to Hassey and asking for a new one. No big deal, you say, that happens all the time. Yes… but in this instance, Harvey doesn’t give him a new ball. Harvey comes out from behind the plate, takes off his mask, starts talking directly to Eckersley, and throws back the same ball Eckersley just rejected.

Why would an umpire do this? What would the two of them have to talk about? And what kind of power move is this on Harvey’s part with the ball? Eckersley doesn’t visibly respond from what we can see on the center field camera, so it’s not a conversation with Harvey – it’s a lecture. What was Harvey saying? Was it about granting time to Davis while Eckersley was already in his wind-up? Why does he walk out in front of the plate, take his mask off, and point at himself while speaking to Eckersley, clearly in an authoritative manner? Is it an “I’m in charge” lecture? Was Eckersley complaining about something, and did Harvey put him in his place?

It’s all speculation, of course, but clearly something caused a future Hall of Fame umpire to come out from behind the plate, with his mask off, at that moment. And regardless of the specifics in that conversation and new ball brouhaha, the inning markedly changes for Eckersley from that moment forward.

04:25 – on a 1-1 count, Davis asks for (and is given) time again, just as Eckersley is starting his motion. The pace of play has slowed down considerably now from Eckersley’s earlier rhythm.

05:10 – Davis walks. Kudos to Davis for patience in this situation, but all four balls were at least four to six inches off the plate. Eckersley wasn’t close.

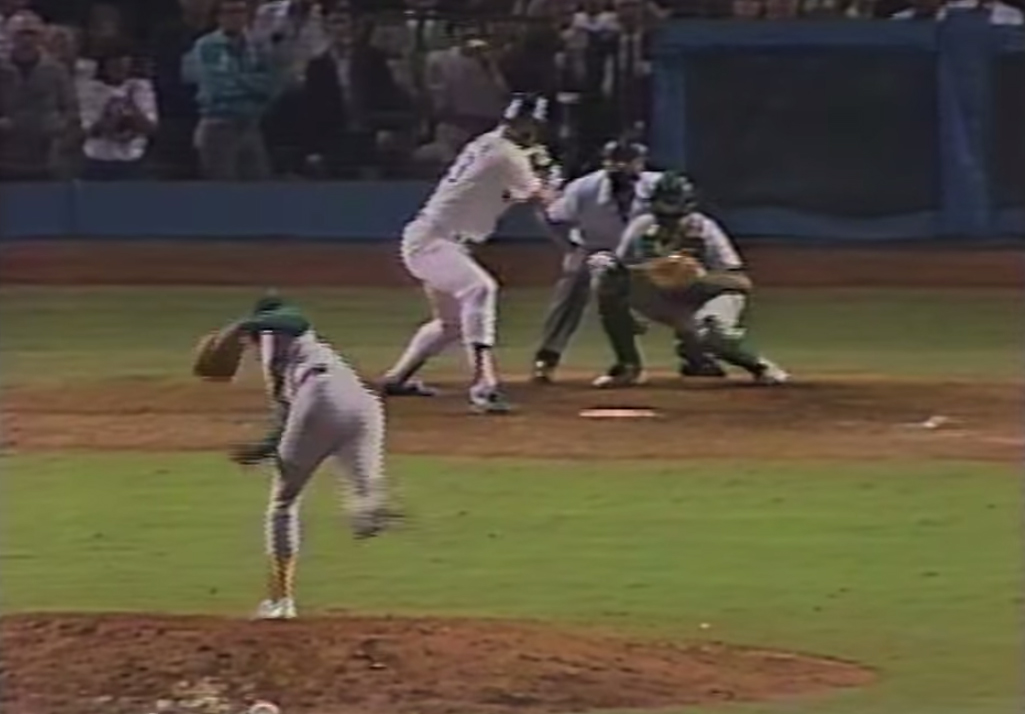

05:17 – And look who’s comin’ up. Speaking of the pace of play, Gibson slows down Eckersley even more than Davis did, having to walk from the dugout as a surprise pinch hitter, apply pine tar to his bat and take practice swings, and then walk to the plate, all while Eckersley waited on the mound. The rhythm Eckersley had on the first two outs has been completely broken by Davis, Harvey, and now Gibson.

06:05 – While Gibson walks to the plate and digs in, we see Harvey walk through the camera shot to his position behind the plate with his mask off, having just come from in front of the plate. Was he at the mound talking to Eckersley? I haven’t seen a second angle that would show where Harvey went during Gibson’s on-deck circle preparation, but it was undoubtedly in the direction of the mound. Harvey wasn’t rising like he had just bent over to clean off the plate; rather, he was in full stride like he’d been walking at least a few steps at that point. Am I reading too much into this? Probably. But something’s up with Harvey and Eckersley.

06:35 – Strike one. I won’t delve into Gibson’s story. It’s been done many times, and I’m focusing on Harvey and Eckersley.

07:00 – Eckersley throws over to first. Oh hey, Mark McGwire.

07:10 – With foul balls being hit and new balls thrown into play, bat boys bringing balls to Harvey, pick-off attempts to first, and Gibson taking time to overcome pain between swings, Eckersley’s rhythm has disappeared. At this point, he’s waiting 20-30 seconds between pitches.

07:47 – Two straight pick-off attempts to first. They know Davis is running.

09:09 – Hassey nearly back-picks Davis at first. Boy, that would’ve been a hell of a way to end a World Series game… right, Kolten Wong?

09:58 – Classic Scully at this point. Gibson shaking his left leg, making it quiver like a horse trying to get rid of a troublesome fly.

10:48 – The 2-2 pitch is interesting. Davis steals second on ball three. Gibson made a veteran (or depending on your perspective, bush league) move leaning out over the plate while Hassey attempted to throw. Hassey, perhaps sensing the lean or looking for a cheap out, pushed his glove hand out to make contact with Gibson, and didn’t throw the ball. Hassey then appealed to Harvey that Gibson impeded his throw, but Harvey didn’t call Gibson out. Should he have?

Major League Baseball Rule 6.06(c) states “A batter is out for illegal action when he interferes with the catcher’s fielding or throwing by stepping out of the batter’s box or making any other movement that hinders the catcher’s play at home base.”

There’s also a comment attached to rule 6.06(c): “If the batter interferes with the catcher, the plate umpire shall call ‘interference.’ The batter is out and the ball dead. No player may advance on such interference (offensive interference) and all runners must return to the last base that was, in the judgment of the umpire, legally touched at the time of the interference.”

Interference in 6.06(c) isn’t dependent on, say, Hassey having to make an actual throw down to second to get the call. So let’s get real about the stolen base: Gibson very clearly stepped on the plate while Hassey was attempting to throw. By the letter of the law, Gibson should have been called out! But be honest – what home plate umpire is going to end a game in the World Series on batter’s interference?

11:04 – NBC replays Gibson and Hassey on the stolen base. Garagiola says, “Harvey said, ‘no, no, [Davis] had the base stolen,’” in regards to a hypothetical conversation between Harvey and Hassey. But Garagiola’s incorrect; whether or not Davis had the base stolen is immaterial, because according to the rule book, Gibson should’ve been out due to the fact that he stepped out of the batter’s box during the throw.

11:58 – High fly ball into right field, she is… gone!

Eckersley had thrown only fastballs (17 straight) up to that pitch, a 3-2 backdoor slider. From Eckersley’s perspective, the call makes sense; you now have first base open, and a right-handed hitter coming up next in Steve Sax. Eckersley, with his stuff and arm angle, was hell on right-handed hitters (remember Jeff Hamilton?). Throwing Gibson a 3-2 slider meant one of two things: either Gibson would leave it alone and walk, bringing a more favorable matchup to the plate for Eckersley, or Gibson would be in front of the pitch, roll over a weak ground ball, and the game would end.

The only problem with that plan? Gibson knew the slider was coming. In Gibson’s own words, told to USA TODAY: “We had a scout, Mel Didier, and he had watched Dennis Eckersley for many years. He came up to me before the Series in his southern drawl, and said, ‘Pardnuh, as sure as I’m standin’ here breathin’, you’re goin’ to see a 3-2 backdoor slider.’ … As soon as he comes set at 3-2, I called timeout and I step out of the box and I’m looking at him and hearing, ‘Pardnuh, as sure as I’m standin’ here breathin’, you’re goin’ to see a 3-2 backdoor slider.'”

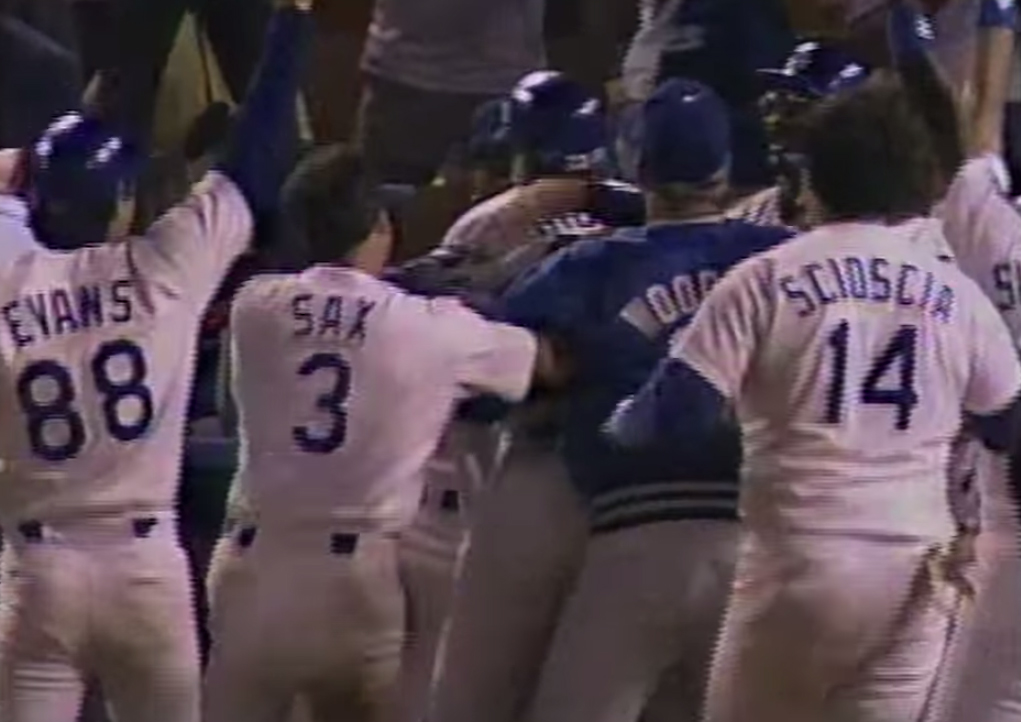

Sure enough, Gibson saw the backdoor slider, Eckersley’s first off-speed pitch of the game. The rest is history. Gibson’s so hobbled he could barely circle the bases, and he gets (softly) mobbed at the plate.

12:51 – Gibson is hugged by Tim Crews. In just his second season with the Dodgers, Crews would go on to put up solid numbers in relief through 1992, and in the spring of 1993, he signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians. On March 23, 1993, he and teammate Steve Olin were killed in a boating accident during Spring Training.

13:00 – Gibson is congratulated by Mike Sharperson. Sharperson played with the Dodgers through 1993, including an All Star game selection in 1992 when he hit .300/.387/.394 in 372 plate appearances. On May 26, 1996, the Padres recalled him from AAA Las Vegas. While driving to San Diego to join the club, he died in a car accident.

13:12 – In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.

13:58 – Garagiola jumps in. “I’ll tell you, there are those who say it’s what happens after the base on balls, but it’s the base on balls that makes it so bad! A home run would’ve tied it, but the walk gives them the win. And Eckersley, who doesn’t walk that many, really gets burned here.”

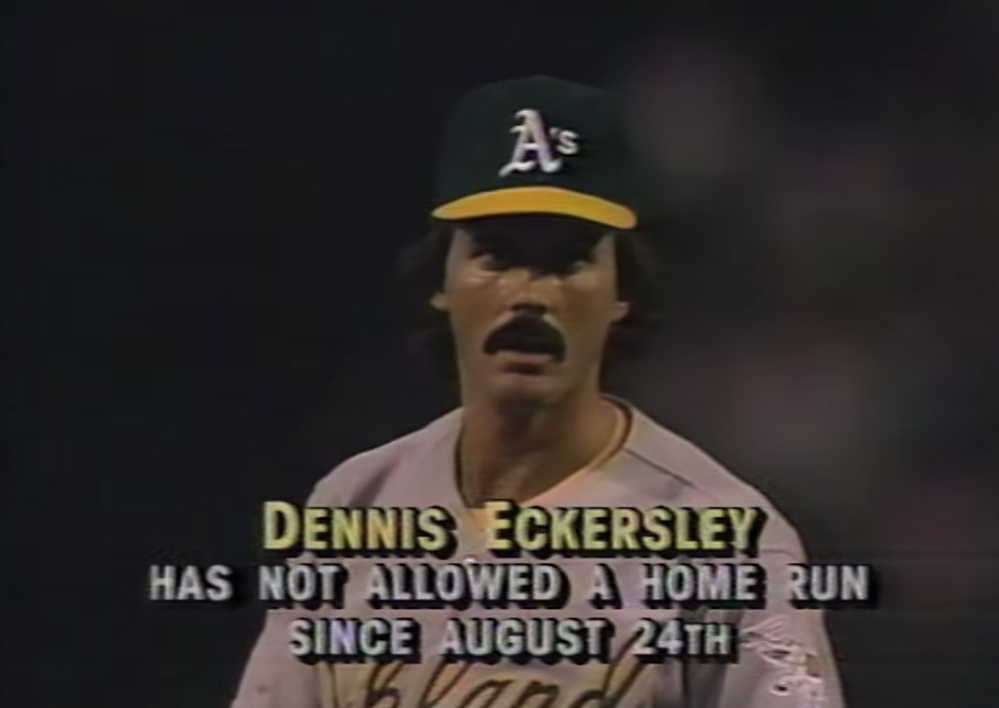

Garagiola was wrong about batter’s interference on the stolen base, but he’s right about this. Eckersley walked 11 hitters in 72.2 innings in 1988, a measly 1.4 walks per nine innings. In fact, in the next three seasons combined, Eckersley would only walk 16 hitters (against 215 strikeouts) in 207 innings, spanning 166 games! He finished his career walking just 2 batters per nine innings, with 738 total free passes over 3,285.2 innings. That career walk rate is video game-level ridiculous, and one of the reasons Eckersley is a Hall of Famer. And yet, he walked Davis.

15:03 – Scully mentions that Eckersley only allowed five home runs in all of 1988. In fact, he only allowed one walk-off home run that year! On July 29, 1988 in the Kingdome, the 62-41 A’s took a 3-2 lead into the bottom of the tenth against the lowly 40-62 Seattle Mariners. Eckersley came in, got two outs, gave up two hits, and then gave up a 3-run walk-off home run to Steve Balboni (but he didn’t walk anybody!).

18:04 – Scully brings up Gibson’s last game-winning home run, which, oh by the way, happened just six days before on October 9, 1988 in New York against the Mets in the National League Championship Series. The Dodgers won both games 5-4.

18:25 – Garagiola hammers Oakland again over pitch selection, arguing the only ball Gibson could get to with his legs the way they were was the slider, and he’s right. The old adage in baseball is never throw something that breaks down and in to a left handed hitter. Eckersley did, and Gibson didn’t miss.

***

Everybody obviously (and rightfully) makes a lot of Gibson’s effort, considering he was up with two bad legs and virtually no power. Others have made much of Davis’ walk, because after all, if he doesn’t get on base the Dodgers don’t win.

And while the stolen base and batter’s interference is an interesting side note, it’s probably just a side note. Was Gibson interfering with Hassey, based on the literal interpretation of the rule book? Yes. There’s no doubt he stepped out of the batter’s box and should have been called out. But would any umpire end a World Series game on batter’s interference? Probably not. And judging by Hassey’s relatively calm reaction to the no-call, the A’s didn’t really expect the game to end there, either. One way or another, it had to be Gibson vs. Eckersley.

The most interesting single event in the inning, and really the turning point, is Davis’ at-bat before the walk. Not nearly enough has been made about the time-called-new-ball interaction between Eckersley and Harvey. It clearly throws Eckersley out of his rhythm. And Harvey takes the time to come out from behind the plate to say something. What went on between Eckersley and Harvey? Why did Harvey refuse to give Eckersley a different ball? What did he say when he came out from behind the plate? Why didn’t Hassey step in to defend Eckersley or talk to Harvey after the interchange?

Today, Harvey is one of only nine umpires enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. He worked as an umpire from 1962 to 1992, and when he retired, he had umpired the third-most big league games (4,673) in history. In fact, in 1999, the Society for American Baseball Research ranked Harvey the second greatest umpire in history. Player polls throughout his career consistently ranked him among the best umpires in the game.

The point is Harvey was more than a good umpire; he was one of the best to ever do his job. He would’ve had a good reason to say whatever he said to Eckersley. By then, Eckersley was an 11-year veteran and a star who would go on to the Hall of Fame himself, so whatever Harvey said couldn’t have on its own shaken him enough to blow the game.

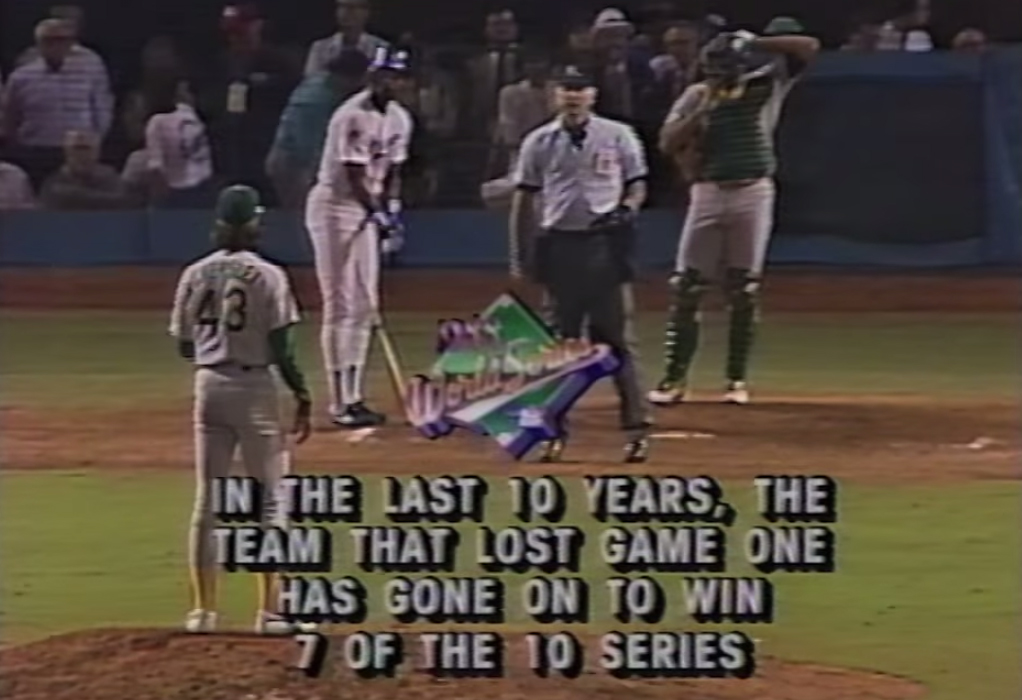

But in a game where inches matter – whether balls and strikes or sliding in to beat a tag – very, very small variables can snowball. Look at the sequence of events from that perspective: Eckersley loses his rhythm on Davis’ time call. Then Harvey lectures him. From there, Eckersley loses just enough focus to throw ball one. So, he nibbles on balls two and three, not wanting to find Davis’ power, and misses both pitches. He loses Davis altogether by not wanting to give in on a 3-1 count, bringing Gibson up.

Gibson takes his sweet time getting to the box, which probably agitated Eckersley, who was known for being quick and jittery. He wanted to get off the field as fast as possible, and here comes Gibson, sauntering and limping. Gibson works the count full in a tough at-bat, and with an open base, Eckersley probably figures, why not, let’s throw an off speed pitch and if it’s ball four, I get to face a righty. Nope. Home run, blown save, game over.

***

So after it happened, did Eckersley ever say anything about the Harvey interaction? Not that I can find. In 1992, when Harvey retired, Bob Nightengale wrote in the Los Angeles Times about how Harvey had been behind the plate in three instances where Eckersley gave up very important runs: the 1982 All Star game, this 1988 home run, and the 1992 All Star Game.

“What’s the deal with him?” Eckersley is quoted as saying in that story. “He’s always behind the plate for me. Get him out of here.” Considering Eckersley’s massive success by 1992, the lack of information about any bad blood between the two men, Harvey’s spotless reputation among players, and that two of these three examples are exhibition games, Eckersley’s quote is pretty clearly tongue-in-cheek.

In 2010, Baseball Hall of Fame President Jeff Idelson caught up with Eckersley and inadvertently mentioned Doug Harvey. Eckersley jokingly reminded him that Harvey was behind the plate for the infamous home run, but that Eckersley “still thought Harvey was an excellent arbiter.”

Not much insight there.

Now, there had been a bean ball battle earlier in that game between starters Dave Stewart and Tim Belcher. Harvey had to warn both teams in the bottom of the first inning. But obviously, Harvey’s conversation with Eckersley wasn’t about hitting batters, as Eckersley hadn’t thrown an inside pitch, and wouldn’t purposely put someone on base in a one-run game.

***

So what should we make of the interaction between Harvey and Eckersley? No one’s blaming Harvey for the home run, obviously; Eckersley gave that up all by himself. And this isn’t a case of an activist umpire inserting himself in the game, considering how minor the interaction was – if it was even malicious at all!

But the Harvey-Eckersley exchange set up the events that followed, and more should have been done at the time to find out what went on between them. It’s a forgotten interaction considering what Gibson was about to do, but seeing the inning as a whole, the Eckersley-Harvey exchange becomes a key moment.

Eckersley cruises through two outs on five pitches, Harvey grants Davis time in the middle of a pitch, and then the wheels fall off for Eckersley. Baseball doesn’t operate in a pitch-by-pitch vacuum; each event creates the next. While Gibson’s home run may have ended game one, that snowball had begun to innocuously roll as soon as Mike Davis called timeout.

Stay with us at Calisportsnews.com as we will keep you up-to-date on all things California Baseball and the rest of the LA sports teams! All Cali, All the time!