100 Years Later: The Franchise- and Baseball-Altering Sale of Babe Ruth

- Updated: January 5, 2020

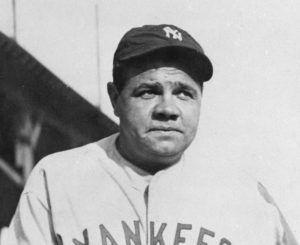

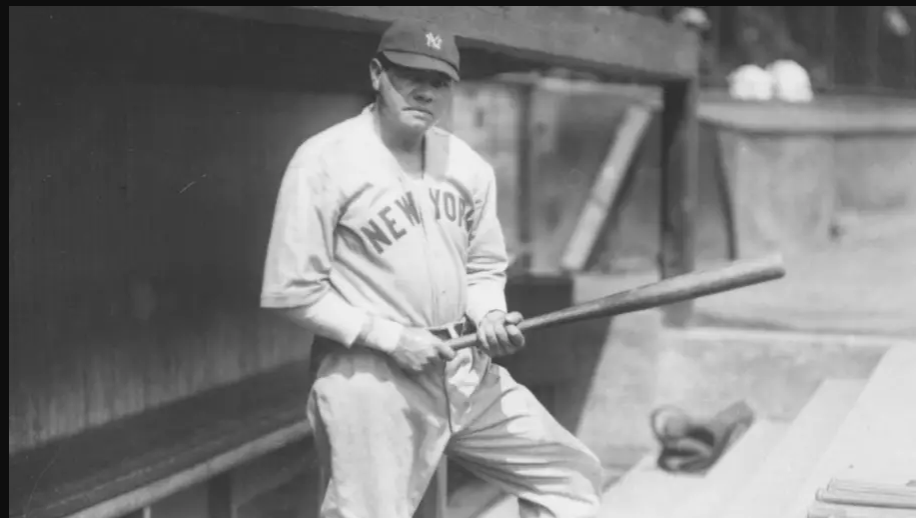

Photo credit: Louis Van Oeyen/WRHS/Getty Images

To most of us, it happened before our time. That, however, has not prevented even the most casual of baseball fans from recognizing just how significant an event this was, both short- and long-term.

Up until 1920, the Boston Red Sox were about as good as it got in the American League. From 1912 to 1918, the Red Sox had won four World Series, three of them in the four years leading up to 1919. Yet, while the likes of Harry Hooper, Heinie Wagner and Carl Mays all contributed to the club’s success around this time, no one was more synonymous to the Red Sox dominance than George Herman “Babe” Ruth.

From his debut with the Red Sox in 1914 at the tender age of 19, Ruth would come to dominate the American League but not with the offensive play as we would later come to know him for. In Boston, pitching was Ruth’s proverbial calling card.

Of their three World Series wins between 1915 and 1918, the Red Sox’ championship success was largely attributed to Ruth in each of these years. As time went on, however, Ruth became more interested in being a hitter, expressing a desire to be in the lineup every day for the Red Sox. The team, however, was not quite as enthusiastic about the transition. This was just one factor that led to arguably the biggest deal in baseball history.

After the deal was made in principle on Dec. 26, 1919, it was on Jan. 5, 2020 when said deal became official — one that would forever change the game of baseball.

Today, on the 100th anniversary of the sale of Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox to the New York Yankees, we look back on this momentous event, a transaction that would shape the future of two franchises in very different ways. For this, I had the honor of speaking with John Thorn, official historian of Major League Baseball since 2011, and Michael L. Gibbons, the longtime Director Emeritus and Historian at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Museum in Baltimore, MD.

A Tale of Two Franchises

I began by asking Mr. Gibbons about the impact this transaction had on both cities and both organizations.

“When Babe Ruth was traded to the New York Yankees and went over to start his career there in 1920, it may be the most significant sports transaction in the history of American sports because it changed the dynamic of the championship-calibre Red Sox team, to say the least,” Gibbons said. “But, the way it impacted New York, and ultimately baseball and the Yankees, was truly significant. The Yankees were a so-so franchise and not all that old leading up to 1920. New York [City] was not the New York that we know today and not the New York that we knew in the 1920’s and even in the 30’s and 40’s. It was not the epicenter of the cultural world.”

New York’s American League club, originally coined ‘the Highlanders’ came into existence in 1903 — just two years after the Red Sox — only becoming known as the ‘Yankees’ a decade later. With that in mind, it could be argued that the Yankees were still trying to find their identity by the late 1910’s, although their 80-59 record in 1919 marked the franchise’s greatest season since 1906. Still, the Yankees had yet to appear in the World Series.

Meanwhile in Boston, owner of the dynastic Red Sox, Harry Frazee, was in a financial squeeze. Needing money to pay off debt on his team’s new ballpark in addition to a side interest, Frazee was looking to make some changes. Despite signing Ruth to a lucrative three-year contract in 1919, the Red Sox owner had second thoughts about keeping his star player.

Major League Baseball historian, the aforementioned John Thorn, explains.

“The Red Sox were paying Ruth $10,000 a year (approx. $149,000 today), on a three-year contract that had begun in 1919, when he set a new home run record with 29,” Thorn said. “Ruth wanted more and promised to stay in California after the winter, making movies and boxing a bit, too.”

But Ruth also wanted to be baseball’s highest-paid player. At that juncture, though, that distinction was held by the polarizing star of the Detroit Tigers, the great Ty Cobb, whose salary was twice what Ruth’s was in 1919. Harry Frazee’s aforementioned financial issues, however, did not help his team’s case for keeping — or rather affording — their star player.

“Harry Frazee needed money to service the debt on Fenway Park,” continued Thorn. “Even after the sale of Ruth, which made the Yankees the mortgagor of Fenway, he still needed capital to fund his theatrical business.”

The Sale’s Significance on a National Scale

Continuing with his explanation of how Ruth’s acquisition helped begin the transition of turning the city of New York into a global phenomenon, Michael Gibbons told me about how the star’s arrival in New York began the transformation shift for the Yankees. This shift would turn a once-average team into arguably the most successful franchise in sports, both on continental and global echelons.

“The Ruth transaction from Boston to New York, when you look at that under a microscope — a baseball microscope — you can certainly say that the star-power and the talent of Ruth coming to New York transformed the Yankees into what became, arguably, the greatest franchise in world sports history,” stated Gibbons. Yet, Ruth’s presence resonated on a national level, as well.

“The other thing is [the United States] was coming out of World War I and America was feeling good about itself because we had victory in the war,” Gibbons elaborated. “We had servicemen returning home, then you had New York, which was starting to become the burgeoning capital of culture and of finance that it later became. But, [New York] also became the epicenter of the Roaring 20’s. It was that dynamic. So, when you take the beginning of the Roaring 20’s and you put Babe Ruth in the mix of all of that, they kind of fed off each other. The city enjoyed a new dynamic and energy and Ruth contributed to it. At the same time, Ruth’s ability of playing for the Yankees had a city fall in love with him and his energy. So, one [form of] energy fed off the other and, you know what, that energy continues to this day.”

The Contributions of Ed Barrow

As for his desire to be an everyday player as a hitter, Babe Ruth’s waning interest in pitching was scoffed at by Harry Frazee. Ed Barrow, though, the Red Sox’ manager at the time, had other ideas.

Credited for the decision to turn Ruth from a pitcher into an outfielder, Barrow noted that his star would be better suited for the Yankees, whose then-home ballpark was much friendlier to long-ball hitters than Boston’s Fenway Park was.

“Ed Barrow, who had overseen Ruth in Boston, moved over to New York [as general manager] and noted that of Babe’s 29 home runs in 1919, only nine were hit at home as Fenway’s right-field wall was very distant,” noted John Thorn. “Ruth would be worth the money he wanted, he recognized, perhaps not to Boston, but certainly to New York, where he might be predicted to hit more than 40 homers. The Yankees played at the Polo Grounds, with a friendly right-field porch. Ruth hit 54 home runs [in 1920].”

After guiding the Red Sox to the World Series title in 1918, Ed Barrow would leave Boston following the 1920 season for New York. There, he was named the Yankees’ general manager — a post he would hold for the next 24 seasons, winning 10 World Series during that stretch.

Barrow would be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953 but passed away that December at the age of 85.

Leaving Boston Behind

From demanding more money to being adamant on playing a new role, it may be argued by some that Babe Ruth, along with his talent and his price tag, came a big ego. Then again, according to Gibbons, Ruth’s departure was more of a result of Red Sox ownership wanting to free themselves of their, for lack of a better term, headache, than anything else.

“I think that Ruth was ready to move on [from Boston]. I don’t think, towards the end of his tenure with the Red Sox, that he enjoyed the way they treated him,” Gibbons began. “By that time, he wanted to be a hitter every day and wanted to be in the lineup every day but the Red Sox were reluctant to that because he was a great pitcher, and I understand that, but they begrudgingly started the transformation of moving him into the outfield and first base to get him into the lineup every day in 1918. They were doing that then and in 1919, obviously, they had done it, but by then, I think [the Red Sox] had wanted to call their own shots in the way they used Babe Ruth and Ruth wanted to do it his way, which I think contributed to Boston’s attitude towards the way he should be managed. That probably had a lot to do with their willingness to part ways with him for money, so I think they just wanted him gone.”

In spite of how his Red Sox tenure ended, though, there didn’t seem to be any hard feelings harbored by Ruth towards his former team.

“Once [Ruth] moved along, did he hold a grudge against [the Red Sox] long-term? I really don’t think so,” Gibbons offered. “Part of that has to do with Ruth being a child, an adolescent in an adult body. It’s like how Babe Ruth would never remember the names of people. He met them, heard their names and then he moved onto the next person, and I think that’s the way it was. In speaking with people who knew Babe Ruth over the years, including his daughter, Julia, I have come to conclude that he really did not fester long-term resentments with almost anybody.”

This was proven in later years with Ruth’s future Yankee teammate, the legendary Lou Gehrig.

“He and Gehrig had a falling out but that falling out was more inspired from Gehrig’s animosity than it was from the Babe’s,” Gibbons pointed out. “I think Ruth would’ve moved along and not worried about it. He would’ve been Lou’s friend again in a heartbeat but Gehrig put a kibosh to that.”

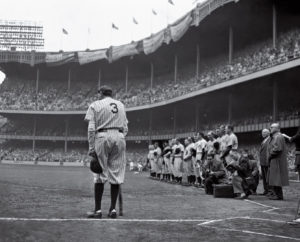

While the two were at odds, Ruth was big enough to attend Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939, greeting Gehrig, who was dying of ALS, on the field just moments before the latter’s now-iconic ‘Luckiest Man Alive’ speech. Yet, while Ruth may not have been known for holding grudges, his daughter, Julia, certainly was — for one organization, at least — according to Gibbons.

“I will tell you this, though: Ruth’s daughter, Julia, did hold grudges and did not like the way the Yankees treated her father after the 1934 season when he was kind of forced out of New York before playing for the [Boston] Braves in 1935,” disclosed Gibbons. “Julia always resented that and if you asked her up to her dying day who she rooted for, she would say the Boston Red Sox and not the Yankees. I think that had to do with her grudge against the Yankees for all those years for how they treated her father at the [end of his tenure].”

While she is no longer with us, Julia Ruth Stevens did live long enough to witness her Red Sox win not one but four World Series titles. She passed away on March 9, 2019 at the age of 102.

The Sale in Hindsight

Looking back on the now-century-old deal, this writer would have been remiss had he not asked Mr. Thorn and Mr. Gibbons how they view the since-infamous sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees.

“The sale of Ruth from Boston to New York was the most momentous in the game’s history, as Ruth became a bigger hero in New York than he could ever have been in Boston,” Thorn started. “But Frazee was bailed out financially by the deal, and he had had reasonable fear that Ruth would not play for him in 1920. So, perhaps not a terrible deal. Look instead at the transaction by which the [New York] Giants acquired Christy Mathewson, a youngster with no wins behind and 373 ahead, for former star Amos Rusie, with 246 wins behind and none ahead.

“The sale of Ruth was not by itself the doom of the Boston franchise; it was the subsequent sales of nearly all its other stars. Boston’s fortunes began to turn with Tom Yawkey‘s ownership and the arrival of Ted Williams [in 1939].”

The comparison to the Christy Mathewson trade made by Thorn is certainly a valid one, underlining that uneven trades are part-and-parcel with professional sports. Mr. Gibbons, on the other hand, held no reservations in calling a spade a spade, although admitted that the deal seemed balanced in the short-term.

“In retrospect, it was a bad trade,” a matter-of-fact Gibbons responded. “But, we know that the Red Sox were perhaps disgruntled with the way that Ruth balked with their management of him and they knew that he could draw a pretty price tag. $125,000 (what the Red Sox received in exchange) was a lot of money back in that day [equivalent to approx. $1.6 million today] and so, the Red Sox got rid of a problem. [Harry Frazee] realized a big payday that may have helped finance his [theatrical] play. The Yankees got a star player without having to send a player to the Red Sox; only money. So, at the time, it may have looked as both sides did okay. However, we now know that both sides did not end up okay as the Red Sox got clobbered. They took a championship team and made it a non-championship team by giving away their best player, their biggest star for money; and the Yankees went on to become the greatest franchise and the most celebrated franchise in the history of sport. So, there can be no question that it was a disastrous transaction from the Boston perspective.”

Of course, like any decision, discussion of the famous — or infamous — sale of Babe Ruth cannot be closed without wondering, what if?

“You have to wonder what would have happened to Boston had Ruth stayed and remained a Red Sock,” continued Gibbons. “It may have been that [the Red Sox] would have become the greatest franchise in sports history; it may be that Boston would have become the cultural epicenter of the United States, if not the world, had Ruth stayed in Boston. The whole scenario transferred south to New York, the city, and the Yankees; and you can only imagine, and guess, what would have happened had that transaction not occurred.

“The Red Sox may have been the cat’s meow for a long, long time — we just don’t know — and New York would have been a great city under any circumstances, just like Boston is today, but it may not have been as great with that mantle of greatness being passed over to the Red Sox. It is intriguing and something to think about.”

A Celebration a Century in the Making

“It’ll be interesting to see how baseball celebrates this: the transaction of and the shifting of Babe Ruth to New York,” Gibbons said of the centennial anniversary. “I think [Major League Baseball] will do a bunch with it because, as we said earlier, this is the penultimate moment, off-the-field, moment, in baseball. So, it’s really important.”

We didn’t finish our conversation, however, until Gibbons revealed some intriguing information about some priceless items related to said deal.

“We just received a donated artifact within the past several months. There were two contracts, two bills of sale: one was the Red Sox copy and one was the Yankees copy. Both of those documents are highly-valued, very valuable artifacts worth lots and lots of money — seven-figure numbers.”

That wasn’t all, though.

“There is a third printed document that we now possess and it was donated by a guy who got his hands on it a while ago. I don’t think a lot of people knew it existed — I didn’t — but it is a recording of the transaction.

“Major League Baseball back in 1919 carrying over into 1920 was not Major League Baseball; it was called something else. You had the American League and you had the National League. So, this printed piece that we have talks about all the transactions that occurred in the game at the top level at the end of 1919 and the beginning of 1920 and it records the sale: ‘Boston, seller, to New York, buyer, for $125,000, George H. Ruth’.

“It makes reference to it but we were going to put that artifact on display probably around Babe’s birthday in February. So, that’s a really nice piece to have because what we do here at the museum, is we take stories like the sale of Babe Ruth to the Yankees and if we have a document to support that, that helps us to interpret the story. People can read about the transaction but also look at something that was pinpointed directly to it. So, it’s a nice piece and it will help us to celebrate the 100th anniversary of it, so it’s pretty cool.

“There’s nothing like [New York]. Babe Ruth has a whole lot to do with the branding of [New York] and simply, he is the symbol of Yankee greatness. He is how [Yankees success] started. So, it’s a pretty profound energy [the Babe Ruth Museum is] going to be celebrating this year with the 100-year anniversary. So, it’s really great.”

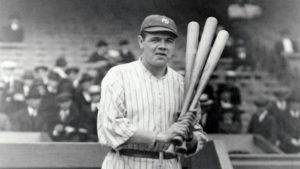

The success of the New York Yankees following the acquisition of Babe Ruth has spoken for itself. Despite falling short in the 1922 Fall Classic, the Yankees would return in 1923, winning the first of their many World Series titles. 1923 also marked the opening of Yankee Stadium, baseball’s first three-tier stadium, which was famously known as ‘The House That Ruth Built’.

The Red Sox, meanwhile, found themselves far removed from their championship days following said sale.

In spite of their dominance in the 1910’s, the Red Sox would not appear in another World Series for over a quarter-century when, in 1946, they lost a heartbreaking seven-game series to the St. Louis Cardinals. Prior to this, the Ruth-led Yankees went on to win 10 World Series, one of which was in 1927. Nicknamed “Murderers’ Row”, the ‘27 Yankees, thanks to their 110-44 record, is still regarded as one of the greatest — if not the greatest — teams in baseball history. Ruth would even make history that year, hitting a then-record 60 home runs in a season. Ruth’s record would stand for 34 years when another Yankee, the unlikely Roger Maris, hit 61 in 1961.

Over the course of the next few decades, the Yankees would keep on winning, although not always led by the gregarious personalities like Ruth was.

Reluctant heroes such as the aforementioned Gehrig and Maris and the great Joe DiMaggio all brought championship success to the Big Apple for the Yankees. The latter, among other achievements, even went on a 56-game hitting streak in 1941: a record that still stands to this day.

Despite having stars such as Jimmie Foxx, Bobby Doerr and the aforementioned Ted Williams, the Red Sox had to wait another 21 years following the heartbreak of 1946 to return to the World Series. The 1967 Fall Classic resulted in yet another seven-game defeat to the Cardinals. Over the years, Boston’s beloved team would provide their loyal fans with more heartbreak.

One example is from 1978 when the Red Sox surrendered a 14-game division lead only to lose in a one-game playoff to, of all teams, the Yankees. The game-winning home run was hit by Bucky Dent — only the shortstop’s fifth that season — leading those in Red Sox Nation to nickname him “Bucky *bleeping* Dent” for years to come.

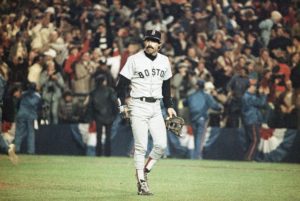

Another example — and perhaps the most infamous — came in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series when the Red Sox, up two runs and one out away from ending their dreaded championship drought, surrendered their lead, and the game, to the New York Mets. The sudden shift in momentum was the result of a series of misfortunes capped off by a soft liner rolling between the legs of first baseman, rest his soul, Bill Buckner. The Mets would win Game 7 two nights later, capturing their first World Series since 1969 and, more significantly, extending the Red Sox’ painful drought.

In 2004, though, after 86 years, the Red Sox mercifully ended their World Series drought. En route to sweeping a familiar foe in the Cardinals in the Fall Classic, the Red Sox would make history in the American League Championship Series. Down 0-3 in the series, the Red Sox, three outs away from elimination came back to win Game 4 and the next three, becoming the first team in baseball history to overcome a 0-3 series deficit to win. Their opponent was none other than the New York Yankees with the series won in The House That Ruth Built.

Perhaps 2004 can’t wash away decades of misfortune but to long-suffering Red Sox fans — this writer included — they wouldn’t have had it any other way. After all, while more World Series wins would have been wonderful prior to 2004, it’s hard to fathom how, and if, 2004 etched itself in Red Sox, and baseball, lore in another fashion.

Had it not been for a baseball owner’s desire to shed some debt and even produce a play — “My Lady Friends” and not “No, No, Nanette” as was believed — it is hard to imagine if we would even be talking about the sale of baseball’s most influential player. Ultimately, it’s hard to imagine if the Red Sox’ World Series losses in ‘46, ‘67, ‘75 and, quintessentially, ‘86, would have been as significant had Babe Ruth not been sold to the Yankees generations earlier.

For someone who has watched Ken Burns’ “Baseball” as often as others may have watched “Star Wars” or “Lord of the Rings”, the game of baseball never ceases to fascinate this writer. This goes especially for the sale of Babe Ruth and how it shaped the game — specifically two franchises — for generations to come.

In recent memory, and to the delight and relief of Red Sox fans, the tide of momentum, if you will, has shifted towards Boston.

Since 2004, the Red Sox have won three more World Series titles, including 2013 when they won at Fenway Park for the first time in 95 years and in 2018 when they set a franchise record en route with 108 regular-season wins. As for the Yankees, while they continue to present competitive teams, the 2010’s marked the first decade since the 1910’s where the Bronx Bombers have not made a World Series appearance.

Over the past century, baseball has seen the most monumental of changes — a list of which much too long to include — and it all goes back to January 5, 1920.

New York may have been transformed into, as Michael Gibbons put it, the epicenter of the world, but Babe Ruth was, and still is, the epicenter of the baseball world. It was his sale to the Yankees that forever transformed baseball into what it is today and, while it may have been to the dismay of the Boston Red Sox, the legacy of George Herman Ruth is, without a doubt, an everlasting one.